“Mr. Yuji Naka is Alright.” – A Retrospective of the Man who Made ‘Sonic’

There are few figures in the gaming industry more venerated among SEGA fans than Yuji Naka. To some, he’s the great-granddaddy of the company’s precious golden — er, blue — goose: Sonic the Hedgehog. To others, he’s the longtime friend and partner of Naoto Ohshima, responsible for helming Burning Rangers, the occasional Yoshi title over at Nintendo, and yes, character designer of Sonic the Hedgehog.

Others still might find their mind conjuring images of the NiGHTS series, whose surreal artstyle and physics-bending gameplay are very much Yuji Naka hallmarks – to the point that his new game with Square Enix, Balan Wonderworld, is purposely emulating them, which can also be observed in … Sonic the Hedgehog.

OK, yes, the Sonic franchise is a major component of Yuji Naka’s career, inescapably so. It is largely credited with being the breakthrough hit that propelled him from lowly programmer to senior producer at SEGA of Japan; and, as recently-retired Sonic voice actor Roger Craig Smith has also discovered, an association with the iconic hedgehog is a hard thing to shake off.

However, it is still but one component of a much larger, richer picture, so with the imminent release of Balan Wonderworld and Yuji Naka ’s much-vaunted return to the 3D platforming genre (check out our preview here), we felt the time was right to invite you to join us for a little delve into the storied history of the man who helped save SEGA.

The Genesis

Born to a traditional family in Osaka, Japan in 1965, Naka gravitated towards what would become his passion from a very young age. As a child, much to his parents’ chagrin, he would spend hours looking through magazines related to computers and digital graphics, a technology which was still very much in its infancy at the time. Programming was at once a simple yet totally foreign idea, and so Naka found himself getting lost in the intricacies of it all, scrawling notes on the pages and attempting to piece together his own imaginary lines of code with very little tech at his disposal.

Such was his devotion that by the time he graduated high school, he had effectively taught himself how to code on a professional level, having honed his skills by writing code during classes and, on the occasion he was able to get onto a computer, studying how they worked.

Of course, by now it was the ’80s, and video games were on the brink of a major comeback after Atari had very nearly nailed the coffin shut on them forever. His magazines of choice were now gaming ones (hey, not unlike our own!) and Naka spent even more time messing around with codes printed in them. He truly felt he had found his calling, and in an incredibly gutsy move for both the culture and the time period, opted to completely skip out on university to pursue his dream. What a trooper.

It wouldn’t be long before he was rewarded. Fate soon came knocking in 1983 when Naka spotted a job listing for a little outfit named SEGA (pretty niche, unlikely you’ve heard of them) who were after junior programming assistants. Though he hadn’t much of a resume, serendipity intervened one afternoon as Naka found himself with nothing to do and decided to apply anyway, doubting he would get the role.

The rest, most would say, is history, but there’s a bit more to it than that. Much to his surprise, Naka was called in for an interview in what was then the diminutive offices of SEGA Japan. The meeting was brief and brisk, and Naka would later recall being thoroughly terrified; but from those humble beginnings, a gaming legend was set in motion.

So desperate was SEGA to break into the burgeoning market that the inexperienced Naka was more or less hired on the spot, and by 1984 he was living his childhood dream, coding for the big boys in blue.

Naka’s first project with SEGA was an unreleased game for the SG-1000, their little-known first foray into gaming hardware. Titled Road Runner, based on a few reports it was a basic racer; Naka was assigned to design its maps, and to this day no known copies have surfaced of this important part of SEGA history.

Tangent: if by some crazy chance someone happens to own Road Runner and is also somehow reading this, get in touch, because trust me when I tell you you don’t know what you have!

Naka drifted in and out of a variety of tasks over the following years, including but not limited to the Master System’s Phantasy Star (with which his bosses were so impressed it earned him a prrrromotion!) and his own personal pet project Girl’s Garden for the SG-1000, a seemingly benign but utterly addictive action game which has you playing a lovesick flower girl. Trust me, it’s pretty great.

But now we come to the real meat and potatoes. In the early ’90s, Nintendo was reigning supreme atop the gaming throne. Mario was the face of the hobby in America. Other tech companies, including Atari (yes, again), Panasonic and Phillips, all threw their proverbial hats into the proverbial ring, in futile attempts to topple the “big N” and their portly plumber mascot. None prevailed.

SEGA, however, figured they had a shot. Under the watchful eye of shareholders, a foolproof plan was cooked up that basically boiled down to three steps:

- Be cheap.

- Beat Mario.

- Make fun of Nintendo.

No exaggeration, no joke, this was the plan. It was drawn up on the office whiteboard.

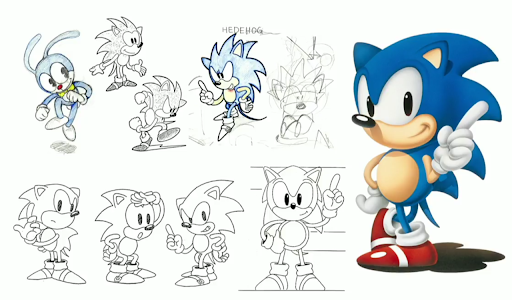

And so a contest was held to come up with a cool, cocky mascot that could overthrow what they perceived to be the sickeningly twee Mario; American kids, they felt, wanted something a bit hipper, a bit edgier. And it was edge they got, so sharp it hurt – or perhaps that was the spines. Yes, after going through several iterations including a rabbit and a tubby scientist who would be retained and used for Robotnik’s design, Ohshima settled on a certain burrowing rodent. Sonic the Hedgehog was born.

Re-enter Yuji Naka. The weighty task of crowbarring SEGA into a market demonstrably resistant to change, and dominated by Nintendo, was dropped at his feet, with nothing other than a few sketches and a basic idea to go on. Fortunately, he had already been working on an algorithm in his spare time for a few years, which allowed a specified sprite to move in a physically accurate curve around loops and S-bends, mapped to a dot matrix. Sound familiar?

Yes, Sonic proved to be the perfect guinea pig for testing this algorithm, and with the assistance of both Ohshima and Hirokazu Yasuhara – forming the genesis, heh, of what would become Sonic Team as we know it – Naka was able to deliver the first game in this now 30-year-old franchise on time. I don’t think you need me to tell you how it turned out, and the impact it had on the face of gaming culture. If only he knew what he was starting.

Sonic’s debut outing was such a smash that Naka was promptly uprooted from Japan and moved to SEGA’s American office, where he was almost immediately put to work on the sequel.

By this point, Sonic Team had officially formed, and it was here that Naka remained for the following decade, a period which saw the rise and fall of the Saturn, the failure of the Dreamcast, SEGA bowing out of the hardware race entirely, and, perhaps most jarringly, Sonic going multi-platform. SEGA, having made their mark by doing what Nintendidn’t, now Nintendid what Nintendo Nintendemanded, Nintendammit.

I jest, of course. The late ’90s and early 2000s were a highly productive time for Naka. Now-cherished classics he helmed back then include NiGHTS Into Dreams, Sonic’s first 3D Adventure, and overlooked gems like Billy Hatcher and the Giant Egg on the GameCube.

Despite the change of scene and fluctuations in a market that was now trending heavily in favor of the three-dimensional, Naka continued undeterred, able to adapt and continue injecting his trademark charm and attention to detail into his projects.

One need only look at the visual flair and tight controls of such critical darlings as ChuChu Rocket! to see that his touch rarely faltered. The creativity of Naka and the versatility afforded by SEGA through their openness to new ideas were a match made in heaven.

However, like many seemingly perfect marriages, it wasn’t to last. Critics were bemused in 2005 when, bending to the requests of several children who had written into the SEGA office asking to see Sonic packing heat (search me!) Naka assumed a senior role over and approved Shadow the Hedgehog.

This bizarre title saw the titular anti-hero gunning down aliens, assassinating the President and cussing up a storm. The utter tonal whiplash and misfire that was the game’s plot, and the lack of the usual care Naka put into his work evident in the gameplay and controls, made many worried that, despite an ingame NPC assuring Shadow that “Mr. Yuji Naka is alright,” the honeymoon period between Naka and SEGA was finally over.

Sadly, it just about was.

I’m not going to rail on Shadow. I know it has its fans. Nor am I going to waste time dumping on what came next for Sonic Team and Naka. We all know this part of the story, and the entire internet has spent the past fifteen years refusing to allow anyone to forget it, long past the point it stopped being funny or original. What’s important is the impact the hellish development of Sonic the Hedgehog 2006 had on Yuji Naka.

Harangued by harsh deadlines and perpetual stalls in progress, as well as a myriad of technical issues caused by unfamiliarity with next-gen hardware and a pervasive sense the project was simply not going to turn out acceptably, Naka at long last packed it in. He had been wanting to start his own company for months at this stage, and ’06 was the straw that broke the hedgehog’s back.

With less than a year until the release of the game, Naka resigned, taking with him “the heart and soul of Sonic,” according to SEGA US CEO Tom Kalinske. Some, perhaps, would argue that part of the soul of SEGA left too, and that the blue speedster himself has never been the same.

Since his departure, Naka has indeed formed his own company, Prope, which is partially staffed by ten other former Sonic Team members and busies itself to this day putting out charming little titles like Ivy the Kiwi? (question mark entirely intended). You’ll also see Naka’s name pop up in the credits of games in the Digimon franchise, and he also lent a hand to Nintendo’s StreetPass series of built-in 3DS apps. StreetPass Quest: Find Mii was of course the best one. No contest.

Most recently and most excitingly, though, was the reveal of Balan Wonderworld, due out in four days’ time. Taking clear cues from NiGHTS, it’s a callback to the ’90s heyday of 3D platforming where Naka found his groove, and features characters designed by Ohshima himself.

It’s a thrilling prospect for SEGA fans and retro enthusiasts alike, and though the demo was met with what we’ll nicely call a mixed reaction, it deserves a look from everyone.

And now we’re all up to date. Yuji Naka’s story is one of perseverance, of taking a chance when all the odds seem stacked against you, of following your oddball dream in the face of resistance. From being a bright-eyed kid scribbling in magazines, to helping create one of the most beloved characters in pop culture, to finally realising his vision of starting his own company, his career has been a rollercoaster, and Balan may just be the culmination of everything that has come before.

It is, after all, Naka’s “only chance” to continue working with Square. So, no pressure there then.

Have you enjoyed this trip through the career of Naka-san? Any fond memories associated with his games? Will you be checking out Balan Wonderworld? Please let us know below!